Amanda J. Bradley

Amanda J. Bradley

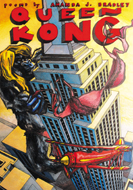

Queen Kong

NYQ Books

Reviewer: Cindy Hochman

Between dolls and dalliance, I begin to realize my body can be a weapon, can be violated, can be impregnated, can make me strong or weak. —“Fourteen”

Even before your mind seizes on the heroic aspects of the comic-book cover of Mrs. Kong as a depiction of towering girl power after an arduous climb, Amanda J. Bradley, whose early years were marked by frequent moves across the whole electoral map with a “goofy, fun, close-knit” family, invokes a life-or-death clinging to what is solid, as if to prevent herself from becoming unmoored. While Bradley’s intense and chock-full-of-details autobiographical poems revel in what she experienced mostly as a blissful childhood (complete with all the Halloween and Christmas trimmings and normal adolescent hijinks), her lament that “I am simply losing people and places, losing people and places” is telling. Moving from place to place was surely a blessing and a curse for her particular sensibilities: the wide swath of American cities she traversed no doubt appealed to the freedom of motion so vital to a child with creative leanings, but perhaps made her more privy and susceptible to an inherent unfairness, bordering on cruelty, in the world, as well as the restrictions of feminine norms and a struggle to find her own place within them. That being said, in the very first poem (“Eight”), she tips her hat to those halcyon days by acknowledging that “We are middle class in the mid-sized town of Anderson, Indiana, / Middle America. I cannot imagine a better way to be young.”

Part One: Childhood

Eight

I am beginning to realize how much I exist. I am really a person,

and these are my thoughts, my hands, my eyes in the mirror.

I care about what I am wearing. I listen to Blondie and the soundtrack

to Grease. In the summertime, we leave home in the morning

and only return for food. We climb trees and shake the limbs hard

or litter the ground with buckeyes …

I try so hard. I am quiet but a leader nonetheless. I can be cruel because

it is important to me to be strong. I am cute and make some people nervous.

Even if you did not grow up in Indiana, Chicago, Ohio, Arkansas, Texas, or Georgia, you will find Bradley’s narrative familiar; it is the diary of girlhood life, with all of its exuberant underpinnings and phases of self-discovery. These effective and affecting poems signify the unfolding maturation of both her inner ponderings and the harsher realities around her. Within these recollections of her callow years, one can readily identify the seeds being sown toward self-actualization and her willingness to leap, full throttle, into it. You can easily picture the poet’s arms, like Queen Kong’s, open to embrace/receive the universe.

Summer 1991

Justin has moved to a studio apartment here … He makes me feel relevant, my life significant in a way I’ve never experienced before. He writes poems and reads novels. I dance around the bed in jean shorts and cowboy boots, tank tops and vintage skirts … It is a summer of rabid fucking. I have never had this much sex. I am enrapt … Physically, I feel glorious. Emotionally, I am consumed by intensity. I am more sober than I’ve been in years. I am always weeping. We drink coffee and smoke cigarettes at Azar’s Big Boy until two in the morning. We are full of hilarity and philosophy … Most evenings, I sit on the stoop of his apartment at dusk to witness what I call “the blue period,” after Picasso. I am tinged with cynicism … I am weeping and splitting and listening to his music and weeping …

Having gone through the obligatory pit stop of religion on the way to rebellion, Bradley follows the biblical dictate of “putting away childish things” as she falls easily into that knotty amalgam of bravura, gleeful brooding, hormones, and coquettish ideation. The poet’s straightforward and self-contained intonation seems deliberate—wildness delivered in a controlled and measured modulation. She neatly walks the line in a dexterous balance between a sharp sense of her own physicality, with a burgeoning attention to her finely tuned intelligence and evolving philosophical beliefs. There is nothing tepid about these times. She is lush and lusty, sultry and dreamy, in love with herself and the boy-of-the-month, and yet fraught with insecurities. She is, of course, invincible. The poems’ soundtrack is an homage to sex and self-medication, with its concomitant mishaps (one of which is a brief but traumatic trip to the psych ward). In the poem “Summer 1993,” with all of the effusive energy of a girl on the cusp of womanhood, she eagerly takes on the role of sexy bookworm, gypsy dervish, and yes, yearning poet, and becomes what she is meant to be: “carefree, risk-taking, beautiful, brilliant.” In the poem “Sophomore Year,” there is a not-so-subtle irony in Bradley and her friends discussing “our idiosyncratic versions of feminist ideals as we bake health bars, brew coffee, and make soup from scratch.” But perhaps most importantly, it is within this restless cauldron (“Graduation”) that she connects the dots between her flowering femininity and a desire to “forge a new way to be in the world.”

Queen Kong

I’ve been shimmying up skyscrapers all my life,

swatting at airplanes that buzz my massive head.

I have been holding tiny men in my palm …

… My drives are ancient and furious.

I peer into the tiny windows of your offices

and see you skitter about in monkey suits.

You think you are making the world go round,

mastering complex transactions, but the world

is simpler than that. It is the stench of my breath

roaring at you through fangs clenched in a wide,

diabolical smile, showering shattered glass at your feet.

In the last section of Bradley’s collection, she is aided and abetted by a gaggle of sister-poets, whose fiery words she uses as epigraphs to sum up and summon an ardent and full-fledged call to arms. In the poem “Totem,” Bradley, as she always has, defies the rigid standards of acceptable behavior of the “gentler sex” by telling the reader to “think females snapping off heads / of males after sex. / Think predation, ensnarement … I want to be so graceful, so ruthless,” and in the poem “Revolting,” she is a “woman crying for the whole world of women to revolt.” Of course, this subversive spirit would not be complete without a final crescendo of sexuality, independence, and that vessel of truth, poetry.

To Twenty-First Century American Women

I am grateful to be born into a country

that educates me, lets me wear mini-skirts

and stilettos or sweatpants with words across

my ass, lets me say ass without stoning

me to death and sleep with whom I please …

Twenty-first century American women, shed

your sense of disgrace. You should not be ashamed.

Take up your pens …

You are open wounds. Bleed healing all over

this country. Plague this country with your disease

until they finally give us the antidotes. You know

the answers. Seek deep for them and then raise

your hands. Make them into fists.

Fight with your fierce voices.

The most striking power of Amanda Bradley’s poems is not whether she has reached that tall building in a single bound, but that, as Queen Kong, she is aware of all the possibilities and potential of those fierce voices—one of the strongest of which is Bradley’s own.