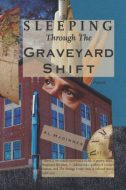

Al Maginnes

Al Maginnes

Sleeping through the Graveyard Shift

Redhawk Publications

Reviewer: Lee Rossi

Even after seven books and numerous chapbooks, Al Maginnes shows no signs of tiring. Sleeping Through the Graveyard Shift, Maginnes’s new book, has an easier, more relaxed feel than his earlier work, yet it is filled with passion and compassion. The subjects are various, the tone meditative, elegiac.

While many of his countrymen continue to fitfully dream the American dream, Maginnes demonstrates time and again just how wide awake he is. “My People: A Citizen’s Report,” for instance, is a dispatch from Carver Country, home to the poor and downtrodden, for whom survival is their only significant achievement: “They are cars left in the rain // with the windows down. Strands of wire stripped / of insulation.” Maginnes knows these people well; he is one of them, “one more tribe flowering out of, then falling // into history, whose other name is dust.”

The next poem in the collection, “Surviving the Storm,” interweaves the story of a giant storm and the lasting damage done by America’s imperial wars. An old tree downed in the storm becomes a metaphor for the republic:

The whole body falling,

like a man

an empire, the collapse

coming

for half-a-century and done in seconds.

…

. . . what killed the tree

did not invade. It was born there.

Yes, he was a teacher for thirty years, but as a young man, Maginnes worked construction, an experience as indelible as Phil Levine’s time at River Rouge. “Where I Was,” for instance, recalls early mornings at the job site, where “ the singular blessing of the unmovable / cold was how quickly it dispersed whiskey fumes / from the night before. “

One hears an echo of Levine’s “What Work Is” in the title and notices a Levine-like fondness for syntax that is easy and colloquial but also sinuous and surprising, as we leap from the end of one line to the beginning of the next.

The Times They Are a-Changin’ – Maginnes knows that as well as anyone. Some of the changes are merely personal, occasion for nostalgia. Yet even nostalgia reveals weightier concerns. Maginnes’s fondness for pop music surfaces frequently. As he reminds us in “Old Records,” those vinyl albums, bought at Colonial Grocery and Woolworth’s, “that tilted stack / of records, the edges / of their cardboard jackets dissolving,” they are

… unwritten chapters

of autobiography, not mine alone

but yours or anyone’s who ever went

into a room to listen to music alone …

“FM DJ’s,” a not quite tongue-in-cheek elegy, traces a similar arc, lamenting the disappearance of those

… voices, rich

as whole notes, [which] drew

smoke-shadows through bedrooms

of solitary teenagers across

half a state.

And with them goes the evidences of who we were when we were young, shiny new miracles of biology:

Vanished like dollar meals,

two for one happy hours, like

forty cent gas, night herons

and Carolina parakeets …

Oops. Suddenly we’re witnessing not just our own obsolescence but also the Sixth Extinction, “technology flown the way of / the imperial woodpecker, the red- / throated woodrail.”

One of the charms of Maginnes’s imagination is its reach, its willingness to mix the tender with the dreadful. How else describe “Where the Famous Dead Have Fallen,” a prose poem which tells how one of Maginnes’s friends used to visit “the field where Rick Nelson’s plane crashed on the last night of 1985” and how later he and Maginnes would visit a small museum which housed some of Nelson’s instruments? “When I thumbed [an] untuned E string . . . [we] stood listening while the plump note resonated far longer than it should, a voice willing itself to go on.”

Music then is not just the soundtrack of our lives, but life itself, declaring who we are at our gooey quivering center. Poetry does the same thing, and so to his list of the gone-but-not-forgotten Maginnes adds a lament for

the noise of a party

where poets spilled drinks

and gossip, where a woman kissed

a man she wasn’t married to.

(“Letter to Logan”)

“I went to that party,” Maginnes confesses. “More than once,” he adds, as he recalls his own “romance with / the regalia of doom.” How do we know we’re alive if we don’t take risks?

And so his heroes are damaged and daring. “Sacrificing Home,” his tribute to one of baseball’s biggest brutes, Ty Cobb, is an unforgiving recital of family dysfunction, Cobb’s mother “shooting the man she married when she was twelve … the man she claimed she believed / an intruder.” She was acquitted but the damage was done; her son,

already known for giving no quarter when

he runs the bases ….

He needs only the little flask

of rage he uncorks each time he crosses a baseline.

Similarly, “Hard Luck,” a multi-part elegy for the boxer Jerry Quarry, is a portrait of dogged perseverance. Quarry had all the will in the world, but also the thinnest skin in boxing. Yet even as he was bleeding all over himself and his opponent, he kept on, “never backing up, waiting / for his opponent to make a mistake.” For Maginnes, Quarry is an exemplar, an American original, and through Quarry he pays homage to “the ones who keep coming, whose art / is perseverance: the graveyard waitress the hot tar roofer . . . / anyone willing to bear the scars of a day’s demands.”

My dad was a boxer and I recognize some of his tenacity in Maginnes’s portrait of Quarry. But we might also recognize a similar tenacity in Maginnes himself. His heroes, his role models may not be perfect, they might not even be heroic in anyone else’s eyes, but as Maginnes shows us, they are as worthy of admiration as any of us, giving what they can, doing their best.